The Revolutionary Thomas Paine

Posted on 12 August 2019

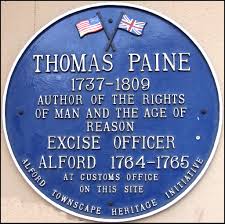

Thomas Paine (1737 – 1809), born in England to Quaker parents, campaigned for revolution first in America and then France.

In the England of Paine’s youth religious intolerance was widespread. Despite the Toleration Act of 1689 that provided legal freedom of worship, Quakers still faced persecution for their dissenting beliefs.

Quaker Childhood

Paine’s father Joseph Pain (the ‘e’ was later added when Thomas Paine arrived in London) was a practicing Quaker and his mother was a member of the Church of England. When the couple were married in her church in Thetford, Norfolk, Joseph was disowned from the Quaker community for ‘marrying out’.

At a young age, Paine would have been aware of the prejudice and discrimination from the dominating Church of England toward the Quakers of Thetford. His lifetime in defense of the underdog might well be traced to these experiences.

Despite never having Convincement to become a member of the Society of Friends, Paine expressed appreciation for the Quakers, especially in their care for the poor and educating children. However, he would later become quite critical of the Society of Friends when it came to the American War of Independence.

In 1762, as a young man, Paine joined the Excise Service as a tax collector and was sent to Lincolnshire. He was first posted to Grantham and two years later was sent to Alford.

A considerable amount of smuggling was taking place at that time. It was at this point whilst collecting taxes, Paine witnessed several injustices of the rich avoiding paying their fair share.

He briefly served in Lewes, East Sussex, before he met Benjamin Franklin at Parliament, in London 1775, who advised Paine to emigrate to America to pursue a career in politics. Paine emigrated and promptly got a job as editor of the Pennsylvania Gazette, which Franklin owned.

After his arrival in America, he soon became highly influential by publishing his pamphlet Common Sense (1776) shortly after the Revolutionary War had begun. The pamphlet did a great deal to swell support for the American colonies becoming an independent country and shift loyalties from British rule to a new republic. The United States of America was the name Paine coined for this new republic.

Within a year his pamphlet had sold upwards of 150,000 copies, a massive amount at the time, stirring both the public and the Continental Congress into action.

The historian Walter A. McDougall said of Paine:

“The American Revolution happened when it happened, because Tom Paine stirred up a storm.”

A. McDougall

Criticizing the Quakers

Paine’s main criticism of the Quakers comes in an appendix to Common Sense entitled An Address to the People called Quakers, where he attacks the society for its lack of support for the Revolutionary War. He argued the Quakers were advising their members to resist the American authorities in carrying out their tasks of defense against British forces.

While he defended the Quaker’s right to refuse to bear arms in any war under any circumstances, Paine thought it treasonous when they prevented others from bearing arms. He wrote:

“Could the peaceable principle of the Quakers be universally established, arms and the art of war would be wholly extirpated: But we live not in a world of angels…I am thus far a Quaker, that I would gladly agree with all the world to lay aside the use of arms, and settle matters by negotiation: but unless the whole will, the matter ends, and I take up my musket and thank Heaven He has put it in my power.”

Thomas Paine

There was a splinter group of Quakers who supported taking up arms who called themselves ‘Free Quakers’, but Paine was not either aware of them or chose not to join them. Paine concludes his criticism of the Quakers in Common Sense more generally, writing:

“The principles of Quakerism have a direct tendency to make a man the quiet and inoffensive subject of any, and every government which is set over him.”

Thomas Paine

Final Years

Living in France for most of the 1790s, Paine becoming deeply involved in the French Revolution. He wrote Rights of Man (1791), in part a defense of the French Revolution against its critics.

This led to his arrest and imprisonment in Paris. Because of his connections with the United States government, Paine was granted a diplomatic release and returned to America.

Paine died, aged 72, in Greenwich Village, New York City. In his will he stated that he wished to be buried in a Quaker burial ground. However, the local Quakers would not allow him to be buried in their grounds, so his remains were buried under a walnut tree on his farm.

Several years later, the writer and orator Robert G. Ingersoll wrote:

“Thomas Paine had passed the legendary limit of life. One by one most of his old friends and acquaintances had deserted him. Maligned on every side, execrated, shunned and abhorred – his virtues denounced as vices – his services forgotten – his character blackened, he preserved the poise and balance of his soul.””He was a victim of the people, but his convictions remained unshaken. He was still a soldier in the army of freedom, and still tried to enlighten and civilize those who were impatiently waiting for his death. Even those who loved their enemies hated him, their friend – the friend of the whole world – with all their hearts. On the 8th of June 1809, death came – Death, almost his only friend.”

“At his funeral no pomp, no pageantry, no civic procession, no military display. In a carriage, a woman and her son who had lived on the bounty of the dead – on horseback, a Quaker, the humanity of whose heart dominated the creed of his head – and, following on foot, two negroes filled with gratitude – constituted the funeral cortege of Thomas Paine.”

Robert G. Ingersoll

Images from www.secularism.org.uk and openplaques.org